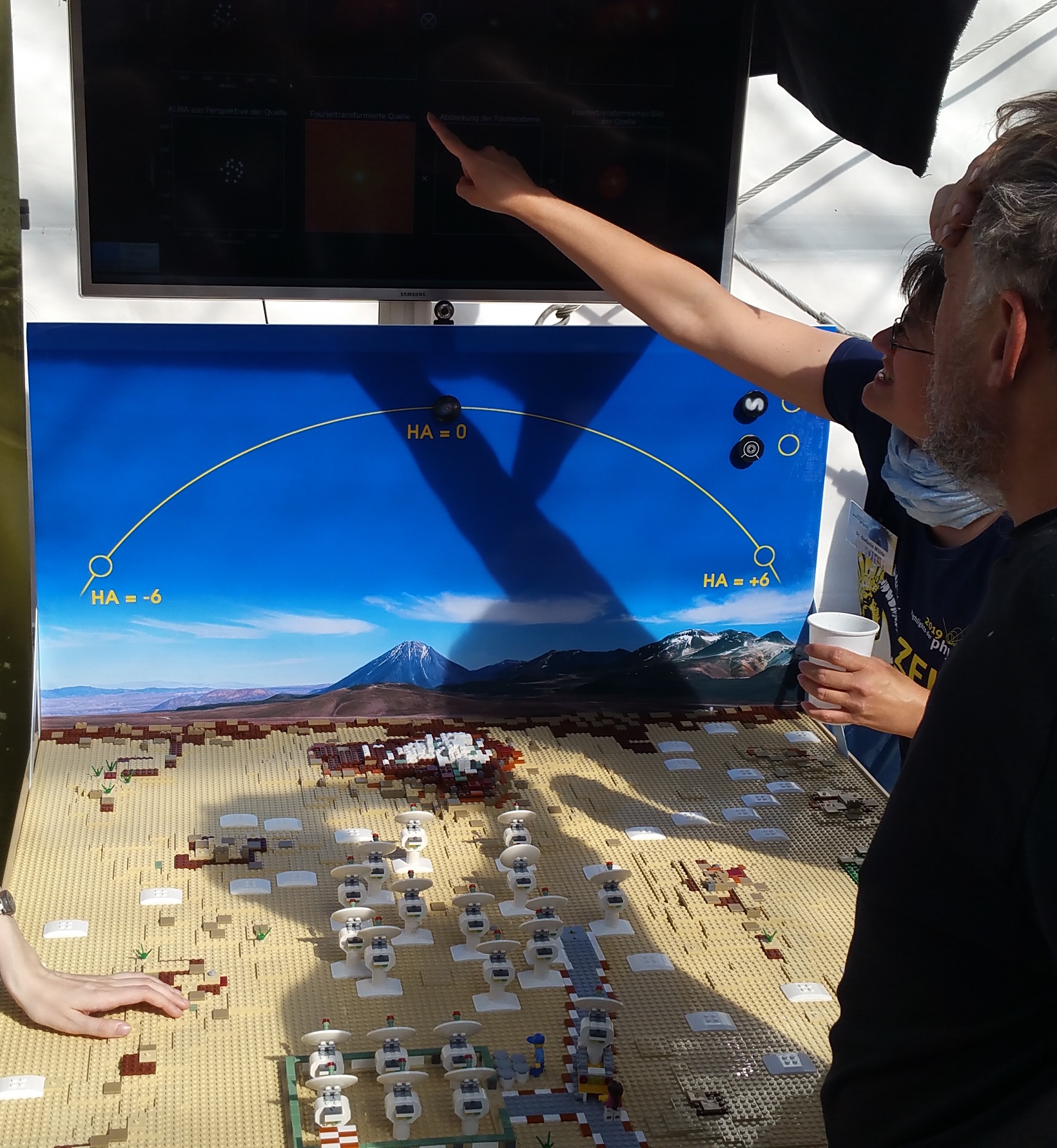

LEGO model of the ALMA telescope array

Introduction

In order to illustrate how an astronomical radio interferometer works, we partially built the ALMA Observatory using LEGO bricks. Although our small telescopes are blind, two microprocessors detect their position and the location of a selected astronomical object in the sky. A computer then calculates the image that ALMA would receive from this configuration.

By changing the number of the up to 19 LEGO telescopes or their relative positions, the calculated image changes. A small image of the celestial object can be moved to various positions on the back wall. The original image and the one observed through our LEGO-ALMA setup are displayed on the monitor. The more telescopes observe, and the better their distribution relative to the object’s direction, the clearer the image. Each configuration change results in a new image being calculated in real time, allowing users to explore what can be observed with a radio interferometer.

Some Technical Details

The sharpness of an image, whether captured by the human eye, a camera lens, or a telescope, depends on the wavelength of the detected light and the diameter of the lens: the larger the telescope, the sharper the image. For example, the human eye has a resolution of one arcminute, i.e. 1/60 arcminute or 1/3 of the diameter of the moon. The resolution improves proportionally as the wavelength decreases and the lens size increases. The smaller the wavelength and the larger the lens, the sharper the image. At a wavelength of 2 cm, the 100-meter Effelsberg radio telescope (Eifel) achieves a similar resolution to the human eye.

Many astronomical objects are much smaller and, hence, observations require an angular resolution of one arcsecond (1/60 of an arcminute) or less. To achieve this, larger telescopes or observations at shorter wavelengths are necessary. The manufacturing accuracy of lenses or mirrors must be better than 1/20 of the wavelength of the observed radiation (wavelength), which quickly drives the technical challenges and costs of larger telescopes to the limits of what is feasible.

Interferometry

Through the clever combination of several small telescopes, a resolution can be achieved that corresponds to that of a much larger telescope; here, it is not the diameter of the individual telescopes that matters, but the maximum distance between them.

Many distributed small telescopes then function like a perforated tlarge telescope.

However, the weakly filled collecting area of such an interferometer comes at a cost: The image has a better resolution (sharpness), but it appears filtered, like through a dirty and perforated pair of glasses. Therefore, the local arrangement of the telescopes is always chosen so that the hoped-for information from the celestial object is optimally visible: a as wide distribution of the telescopes as possible to detect sharp details, where the more extended structures fade away, or vice versa. The true overall image of the source is difficult to capture with an interferometer, but it provides us with the insight of the smallest details that would never be visible with a (realisable) single telescope.

The Performance

The computational effort of an interferometer is enormous. Each telescope has a receiver that continuously registres the radiation intensity and wave phase of the targeted radiation source and transmits this information to a central "correlator." Divided into narrow frequency intervals, this correlator (i.e., it multiplies and averages) pairs the signals of all the telescopes (for the 50 ALMA telescopes, this means 50*49/2 = 1225 pairs) and averages the values over a few seconds. In the process, ALMA stores about 500 megabytes of measurement data per second. From these so-called visibilities, an image of the celestial object can be calculated – as mentioned, it is seen through a kind of filter.

Our LEGO model also calculates the observed, filtered image of a selectable object, such as a spiral galaxy, an S-shaped structure with embedded point sources, a geometric pattern, or directly captured viewers through a camera.

The 19 LEGO telescopes can be positioned at 43 predetermined locations. The actual ALMA has 66 telescopes and 192 positions (pads) at a maximum distance of 16 km.

The design and construction are the responsibility of the research group led by Prof. Bertoldi at the Argelander Institute for Astronomy at the University of Bonn, particularly Toma Badescu, Philipp Müller, Dr. Benjamin Magnelli, and Dr. Stefanie Mühle.

This website has been translated from German into English in part with ChatGPT 4.0 , OpenAI’s large-scale language-generation model. The translation draft has been reviewed and edited by the webmaster (further information see imprint).